Download Course Syllabus (PDF)

1 Connolly's Stardust Room

1184 Tremont St

1957 - 1998

Historical Marker by Erin Carr, M.A. Candidate, Public History

History

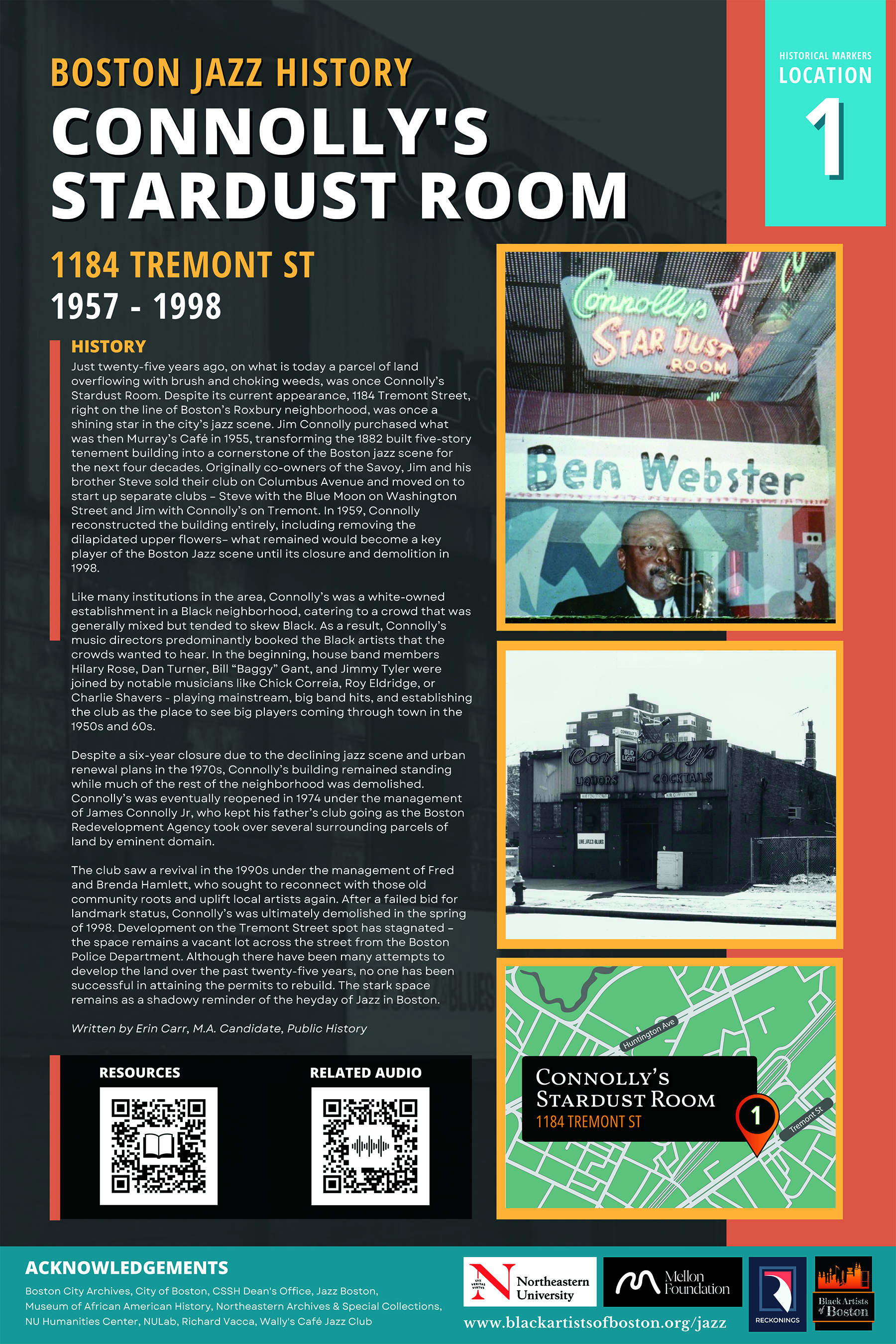

It may not look like it now, but 1184 Tremont Street in Roxbury was once a shining star in the Boston jazz scene. What is today an abandoned parcel of land, overflowing with overgrown brush and choking weeds, was Connolly’s Stardust Room just 25 years ago.

Jim Connolly purchased what was then “Murray’s Café” in 1955, transforming the 1882 5 story tenement building into a cornerstone of the Boston jazz scene for the next 4 decades.1 Originally an owner of the Savoy, Jim and his brother Steve sold their club on Columbus Avenue and moved on to start up separate clubs – Steve with the Blue Moon on Washington street and Jim with Connolly’s on Tremont.2 In 1959, Connolly removed the dilapidated upper floors and what remained would become a facet of the Boston Jazz scene until its closure and demolition in 1998.3

Like many institutions in the area, Connolly’s was a white-owned establishment in a black neighborhood, catering to a crowd that was generally mixed but tended to skew black. As a result, Connolly’s music directors predominantly booked the black artists that the crowds wanted to hear.4 In the beginning, house band members Hillary Rose, Dan Turner, Bill “Baggy” Gant, and Jimmy Tyler were joined by notable musicians like Chick Correia, Roy Eldridge, or Charlie Shavers - playing mainstream, big band hits and establishing the club as the place to see big players coming through town in the 1950s and 60s.5

Despite a declining jazz scene and urban renewal plans in the 1970s, Connolly’s remained standing while much of the rest of the neighborhood was slated for demolition. Following a brief 6 year closure, Connolly’s reopened in 1974 under the management of James Connolly Jr, who kept his father’s club going while the Boston Redevelopment Agency took it and several surrounding parcels of land by eminent domain.6

The club saw a revival in the 1990s under the management of Fred and Brenda Hamlett, who sought to reconnect with those old community roots and uplift local artists again. After a failed bid for landmark status,7 Connolly’s was ultimately demolished in the spring of 1998.8 Development on the Tremont street spot has stagnated – the space remains a vacant lot across the street from the Boston Police Department. Permits are currently pending for development of the space, though not for the first time in the past 25 years.9 The stark space remains as a shadowy reminder of the heyday of Jazz in Boston.

Citations

1. Boston Landmarks Commission, Environmental Department, City of Boston. “Report on the Potential Designation of Connolly's Bar” (1997), 4.

2. Ibid, 10.

3. Vacca, Richard. “A Short History of Connolly's.” RichardVacca.com, November 7, 2022. https://www.richardvacca.com/a-short-history-of-connollys/.

4. Ibid.

5. Vacca, Richard. The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962. Troy Street Publ., 2012, 145-46.

6. Vacca, “A Short History of Connolly’s.”

7. To view the landmark proposal, see Boston Landmarks Division, “Report on the Potential Designation of Connolly's Bar”

8. Vacca, “A Short History of Connolly’s.”

9. Darryl C. Murphy, “Vacant for Decades, a Key Parcel in Roxbury May Finally Come Back to Life,” WBUR News (WBUR, October 27, 2021), https://www.wbur.org/news/2021/10/27/vacant-for-decades-a-key-parcel-in-roxbury-may-finally-come-back-to-life

2 The Pioneer Jazz Club

2 Douglass Park

(Previously 2 Westfield St)1

1940s - 1974

Historical Marker by Claire Lavarreda, Ph.D. Student, World History

History

At this site in the 1940s, pharmacists Bal & Shag Taylor opened the famous and mysterious Pioneer Jazz Club. The spot was host to a three-story after-hours haven, filled with good drinks, lively music, and political activism. Most notably, the Pioneer Club was home to the United Democratic League, and served as a site of political collaboration, aiding Black politicians and legislators like Judge Elwood McKinney, Mayor James Curley, and State Representatives Lincoln Pope, Royal Bolling Sr., and the Alfred Brothers in gaining their political offices.2 The club also commanded prominent musicians like Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday, who frequented this club when they made their way to Boston, making it a popular jaunt for all residents wanting the best of Boston’s nightlife. The club, which was known for its pink lights and dark black interior, became an exclusive place to see and be seen, allowing only “in-crowd” into the spot, but only after inspection through a peephole in the club’s locked door.3

Sadly, Shag Taylor passed away in 1956, but Bal was able to hold on to the club for almost two decades on his own, until his own passing in 1974, which coincided with the demolition of the club that same year.4 Still, it lives strongly in the memory of Boston’s jazz community: Matthew E. Goode, a participant in the Lower Roxbury Black History Project, once said “... it was the deep dark secret in Roxbury for people – and people came from everywhere to go to the Pioneer Club.”5 This was the Pioneer Club: daring, elusive, and gone, quite literally, in a puff of smoke.

Citations

1. G.W. Bromley, Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay: From Actual Surveys and Official Plans. (Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley & Co, 1938), 30.

2. Bob Hayden, “Boston’s Black History: The Taylor Brothers,” Bay State Banner, September 21, 1978, 6.

3. Thomas F. Mulvoy Jr., “FYI,” Boston Globe, March 23, 2003,1-2.

4. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Belmont: Troy Street Publishing, 2012), 145.

5. Richard Vacca, “July 18, 1974: Good Night to the Pioneer Club,” Richard Vacca (blog), July 18, 2013, https://www.richardvacca.com/july-18-1974-saying-good-night-to-the-pioneer-club/; Matthew E. Goode, interview by Lolita Parker Jr., December 26, 2008, interview M165, transcript, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, 22.

3 411 Lounge

411 Columbus Ave

1948 - 1968

Historical Marker by Samantha Frost, M.A. Student, Public History

History

Boston’s 411 Lounge, located at 411 Columbus Avenue, was a notorious site during the height of Boston’s jazz scene, but not necessarily for its music– it was the site of illicit activities both inside and outside of the club’s walls. Originally opened as the Monterey Café in 1937, it then became the Golden Café in 1944. Two years later, it was renamed the Sunnyside Café in 1946 before settling into the 411 Lounge in 1948 until its closing in 1968. The club hosted many talents, including local musicians like Eddy Petty, Hank Mason, “Fat Man” Robinson’s Quintet and Sam Rivers, Ray Perry and the Perry Brothers Band, and even nationally recognized acts like Mabel Simms and Billy Eckstine.1

By the 1950s, less live music took place at the 411, as its owner, Abraham “Abe” Sarkis (b. 1913), became more involved in bookmaking and Boston’s seedy underbelly of illegal activity.2 Consequently, the 411 had become a hotbed of gambling, drugs, and alcohol, among other illicit activities, and the music was sent to the back burner. Eventually, Sarkis was arrested and the club closed its doors less than a year later and remained unoccupied until 1970.3

In addition, the Union Methodist Church a few blocks down at 485 Columbus Avenue began sponsoring affordable housing as part of the urban renewal projects of the 1960s and 1970s.4 In the early 1970s, Methunion Manor Housing Cooperative was erected, changing the face of a once notorious (and now mostly forgotten) site in Boston’s underground. While the 411 may not have been at the center of the jazz scene, it remained an important site for understanding the dynamics of Boston’s social, economic, and cultural climate

Citations

1. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Massachusetts: Troy Street Publishing, 2012), 142 and William Buchanan, “411 Lounge Opened Window on Life as Few Ever Saw It,” The Boston Globe, June 8, 1970, 5.

2. “Convicted Bookie Dies Awaiting Trial in Gambling Case,” The Patriot Ledger, June 7, 1991, 8.

3. Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles, 142.

4. J. Anthony Lukas, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1985), 184.

4 The Ken Club

58 Warrenton St

1939 - 1949/1950

Historical Marker by Oscar Navarro, Ph.D. Student, Criminology and Justice Policy

History

From the late 1930s through the 1950s, at what was once 58 Warrenton St, stood a jazz club that was at the hub of Boston’s exploding jazz scene. Opening in 1939, tucked in the basement space of Hotel Broadway, the Ken Club was home to many hallmark names in the Boston jazz scene, such as Frankie Newton, Max Kaminsky, Sidney Bechet, Wild Bill Davidson, J.C. Higginbottom, Pee Wee Russell, Red Allen, and Pete Brown.1 2 In operation for just over a decade, the Ken Club was cemented in jazz history for its popularization of the Sunday Jam Session. Musicians from all over Boston came to improv and innovate– pushing the limits of their creativity.3 The Ken Club’s Sunday Jam Sessions also gave a chance to up-and-coming musicians to play alongside with the titans of the scene.

The popularity of the jam sessions brought together many high-profile jazz musicians from all over, especially big-name talents from New York. As the innovators of the scene, many other local clubs began their own jam sessions, such as Hotel Buckminster, Storyville, the Hi-Hat, and notably, Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club which still holds sessions for young musicians to this day.4 The Ken Club’s Sunday jam sessions were incremental to fostering the local jazz community and elevating new musicians to new heights. Despite its success, Boston’s jazz scene began to wind down as many musicians left Boston for cities like New York, Chicago, and New Orleans where there were more opportunities for recording and live performances.5

Subsequently, the Ken Club’s Sunday Jam Sessions and live shows began to dwindle, and by the 1950s the Ken Club was no more. Later redevelopment of the area resulted in major change: Carver St. and Broadway St. are gone, and Warrenton St. no longer connects with Tremont St. Instead, the current space where the Ken Club and Hotel Broadway once was is now Elliot Norton Park.6 Although no longer in existence, the Ken Club’s influence on Boston’s jazz scene lives on. This is seen through many of Boston’s young and innovative musicians at the local colleges in the area and cemented by the numerous living legends inhabiting the neighborhood.

Citations

1. Richard Vaca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962. (Concord: Troy Street Publishing, 2012).

2. Richard Vaca, “Apr 19, 1942: First Sunday Jam Session at the Ken Club.” RichardVacca.com, April 20, 2013.

3. Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles

4. Ibid.

5. J.R. Carroll, “Book Review: The Boston Jazz Chronicles -- Indispensible History.” The Arts Fuse, November 19, 2012.

6. Ibid.

5 Tic Toc Club

245 Tremont St

1941 - 1944

Historical Marker by Catarina Tchakerian, M.A. Candidate, Public History

History

The Tic Toc Club, located at 245 Tremont Street across from the Metropolitan Theatre (now the Wang Theatre), burned brightly on the Black jazz scene in Boston between 1941 and 1944. Although short-lived, the Tic Toc Club was arguably the premier jazz club in Boston, hosting big-name performers like Tiny Sinclair, Louis Armstrong, Bob Astor, Peter Herman, Mal Hallett, Ella Fitzgerald, and Andy Kirk. The venue promoted its name-band bookings, often marketing the phrase “Always a Famous Band” alongside the club’s name. The Tic Toc Club was owned by brothers Ben and Jack Ford, who were also the agents for several famous musicians’ bookings. Their positions relative to these musicians aided in securing their performances at the Tic Toc Club. With a long list of available artists, the club booked long sets of six acts, requiring no cover charge, starting as early as 2 PM on Sundays.

Despite being legally formally integrated, and featuring major Black jazz artists of the day, the Tic Toc Club was not so equitable in practice. There was a legal conflict at the Tic Toc over segregated seating for Black patrons in 1943, as well as separate incidents of racially motivated agitation throughout its operation. The fraught racial dynamics of the Tic Toc Club pointed towards a greater issue of systemic racism in America, where Black performers were revered for their talents, and yet Black patrons were barely allowed inside the club.

The original Tic Toc Club had a short run: the Fords received an eviction notice in September of 1944 and the club closed on October 4, 1944. This closure did not, however, signal the end for the Tic Toc brand. Different iterations of the club persisted through the 1960s, rebranded as the Tic Toc Lounge, the Tic Toc Restaurant, and the Petty Restaurant. It eventually shifted management, owners, and addresses, too, hopping from 245 Tremont Street to other nearby addresses until its branch-offs finally closed. Today, the address of the original Tic Toc Club has been subsumed into the luxury hotel accommodations of the W Boston, a modern high-rise divorced from the historic legacy on which its foundations lie.

Citations

1. Richard Vacca, “August 7, 1944: Hines Plays It Cool at the Tic Toc,” Richard Vacca (blog), August 7, 2023, https://www.richardvacca.com/.

2. Ibid.

3. See “Display Ad 13 – No Title,” Daily Boston Globe, November 28, 1942, 10; “Display Ad 14 – No Title,” Boston Globe, June 21, 1960, 11; “Display Ad 33 – No Title,” Daily Boston Globe, November 11, 1942, 24; “Display Ad 33 – No Title,” Daily Boston Globe, October 21, 1942, 21; “Display Ad 37 – No Title,” Daily Boston Globe, November 26, 1942, 28; “Display Ad 49 – No Title,” Daily Boston Globe, October 30, 1942, 36.

4. Richard Vacca, Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937-1962 (Belmont: Troy Street Publishing, LLC., 2012), 73; Vacca, “Hines Plays it Cool.”

5. Richard Vacca, “Hines Plays It Cool.”

6 Storyville

Copley Square Hotel (1950, 1953 - 1960)

Hotel Buckminster (1951 - 1953)

1950 - 1960

Historical Marker by Kiley Atkins, M.A. Candidate, Public History

History

The basement venue at the Copley Square Hotel once housed the legendary jazz club Storyville. Opened in October of 1950 by music producer George Wein, the club was legendary for its exceeding talents that passed through, and the ways in which Wein encouraged people to listen to and appreciate jazz music.1 Wein had his finger on the pulse of American jazz and a good grace about him, which in turn, allowed him to befriend and book some of the best names in music.

This Copley Square location was the original home to the club, although for a bit of time the club was moved to Hotel Buckminster a few miles away in Kenmore Square (not too far from Fenway Park).2 Although a relatively short period of only two years, that location of the club saw some of the largest acts in jazz music at the time, such as Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Erroll Garner, Charles Mingus, and many more. When the club returned to Copley Square, it would continue to command the same large acts, including Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington.3

More than anything else, Wein understood music, and knew how to shift how people call patrons into what he believed was one of the purest American artforms-- thusly making the club, according to The Boston Globe “Boston’s temple of jazz.” The paper let readers know, if you wanted the best jazz in the area, this was the place to go.4

Wein’s helm and influence on the music industry meant that Storyville provided a place where all jazz musicians could be respected by both management and patrons, regardless of how established they were. And provided a home for local artists. Additionally, he fostered a love for jazz among Boston’s youth, hosting Teen Jazz Club, which allowed teens to listen to performances and get a chance to practice with and learn from established jazz musicians.5 It was here that important intergenerational bonds were made, greatly influencing a new crop of musicians who would go on to pay respects to the greatests.

Though it was only operational for a relatively short time, the impact of Storyville is still felt by those who visited. Its legacy as a place of respect, community, and art is truly unique and it has not yet been replicated.

Citations

1. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937-1962, (Concord: Troy Street Publishing, 2012), 232, 235

2. Ibid., 229, 231-232

3. George Wein with Nate Chiene, Myself Among Others: A Life in Music, (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2004), 76, 87-88, 94, 109.

4. Cyrus Durgin, “Jazz Moves to Newport as Serious Music Form-Records Reviewed: Festival at Newport, or Jazz Now a Serious from of Music” Daily Boston Globe, June 20, 1954.

5. Vacca, 231.

7 The Jazz Workshop

733 Boylston St

1963 - 1978

Historical Marker by Kristin Økland, Ph.D. Student, World History

History

733 Boylston once was home to the last iteration of Boston's Jazz Workshop, first created by local Bostonians Charlie Mariano and Herb Pomeroy. Under fellow Boston resident Fred Taylor's management, the Jazz Workshop at 733 Boylston featured jazz and blues musicians from 1963 to 1978 while hosting other bands in the Paul's Mall music hall which occupied the building's first floor. Set lists from this time include Charles Mingus, B.B. King, and Mongo Santamaría.

When The Jazz Workshop first opened in 1965 yet another Bostonian legend was born. The Jazz Workshop was located in 733 Boylston's Street's basement while Paul's Mall, a music hall, hosted many different set lists in the 1970s. The Inner Circle Restaurant at #733 and 733 Cinema was also included in this building complex, offering Bostonians a venerable artistic buffet. Both venues were Fred Taylor's brainchild.

Fred Taylor was born in 1929 to Jewish parents who worked as upholsters and mattress sellers in Newton. Taylor attended many jazz concerts in his youth and was no stranger to the concert scene; as an adult, music promotion is where Taylor eventually found his specific niche. The Jazz Workshop flourished under Taylor from 1963 to 1978, but even after the Jazz Workshop and Paul's Mall closed its doors in 1978 Taylor went on to promote more jazz music. Schuller's Jazz Club -- now located inside the DoubleTree Suites Hotel at 400 Soldiers Field Rd, Boston -- became Taylor's focus for jazz in Boston from the early 1990s until 2017. Outside of Boston, Taylor helped produce the 2001 -- 2007 Tanglewood Jazz Festivals located in Lenox, MA. Taylor would sadly die in 2018, but his work and influence lives on in Boston's music and jazz scene.

8 The Stable

20 Huntington Ave

April 1954 - Late 1962

Historical Marker by Anna Halgash, M.A. Candidate, Public History

History

Established in April of 1954, The Stable was a basement bar-turned-jazz club at 20 Huntington Avenue in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston. The Stable was also once the site of the Jazz Workshop, where locally famous Jazz musicians Ray Santisi and Varty Haroutunian once taught.1 While The Stable was not as big a name as some of the other area clubs, it was a staple of the local Boston jazz community, and many touring musicians frequently visited The Stable and performed for their warm audience.2 The club’s friendly rivalry with the neighboring Storyville Jazz Club drew over the latter’s performers during their performance breaks.3 Although the club itself did not attract many big-name performers, many of its house musicians would go on to perform with top acts, including major stars like Tony Bennett and Frank D’Rone.4

Over time The Stable’s local audience grew from jazz-savvy locals in the neighborhood expanding to students at local colleges like Harvard and Boston University and beyond to Boston’s other neighborhoods and the surrounding cities, including Roxbury, Roslindale, and Newton.5 The Stable’s local focus kept prices financially accessible for working-class patrons and attracted young musicians looking to gain new audiences. The interior of the space was described as “a pine-paneled room (ninety-seat capacity) filled with small, sturdy tables, red-padded kitchen-type chairs, a rumpus room-sized bar with some half-dozen stools, and a tiny bandstand.”6

Members of the club’s most notable band, The Stablemates (who would eventually tour the country as the Herb Pomeroy Orchestra), would go on to become influential faculty at the world-acclaimed Berklee School of Music.7 As Berklee is known for jazz, the members had a significant impact on the education of the next jazz generation. In many ways, The Stable was the ‘unsung hero’ of refining, mixing, and modernizing jazz’s sound in the 1950s.8

Despite this influence, the club dwindled in popularity as local jazz musicians migrated to new competing cities like New York and local music tastes evolved towards folk, rock, and rhythm and blues.9 While the house band The Stablemates were able to able to gain ownership of the club after the owner Harold Buchhalter left for a new club on Boylston Street in 1959, the club would eventually close in 1962, and later be demolished in 1963 for the building of an onramp for the Massachusetts Turnpike, ironically leading drivers to New York.10 Today, the on-ramp sits between The Westin Copley Place and Trinity Place Condominiums.

Citations

1. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Belmont: Troy Street Publishing, LLC, 2012), 210, 211.

2. Vacca, 212, 213, 221.

3. Ibid., 222.

4. Ibid., 221.

5. Hayim Kobi, “Tom Wilson, Producer: Part 1,” The Music Aficionado: Quality Articles About the Golden Age of Music (blog), June 30, 2021.

6. Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962, 212.

7. Ibid., 210, 212, 214, 217, 218, 220.

8. Ibid., 215.

9. Ibid., 220, 223, 225.

10. Ibid., 224, 225; Richard Vacca, “John Neves: ‘His Time Was Impeccable,’” Richard Vacca (blog), July 17, 2019.

9 The Savoy Cafe

410 Massachusetts Ave

1947 - 1958

Historical Marker by Avery Ferro, M.A. Candidate, Public History

History

Today, 410 Massachusetts Avenue is the site of a barber shop. The building appears small and the location inconspicuous. One might never guess that in the 1940s, this space was considered one of the most important venues of the Boston jazz scene: The Savoy Cafe. Dubbed the home of Boston jazz, the Savoy was a small, narrow room with a bandstand standing proudly in the middle - a bandstand that would welcome many well-known artists during its 15 years of operation. With mirrors and pictures of jazz musicians lining the wall, Downbeat Magazine - a contemporary music magazine - described it as one of the “cushier” clubs. However, this was not its first location. The Savoy originally opened on Columbus Avenue, just around the corner from this spot in 1935. Seven years after the Savoy’s opening, in November of 1942, the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire occurred killing 492 people and, consequently, stricter safety guidelines for nightclubs were implemented across Boston. The Savoy’s original location did not have the proper exits to meet these guidelines and, thus, moved to Massachusetts Avenue in Spring of 1943.

The Savoy Cafe was owned and managed by Steve Connolly. Despite its notable lack of room for dancing, Connolly wanted live music to be the heart of the Savoy and, in turn, the Savoy became the heart of the Boston jazz scene itself. The Savoy proclaimed itself the “maker of bands” - Sabby Lewis and his band being the most prominent one to emerge. Lewis was hired by Connolly and was a fixture at the Savoy for many years during which he gained great popularity in Boston. The Savoy was also the venue where Frankie Newton rose to local fame. Later, when the club made its move, it saw performances from other artists such as Mae Arnette and Pete Brown. The Savoy not only attracted famous Boston performers but well-known patrons as well: before his days as Malcolm X, Malcolm Little was known to have frequented the club and even wrote about it in his autobiography. What is more, the Savoy was also a safe haven for patrons who may not have been welcomed elsewhere at the time. It was known to be friendly to same sex couples and one of the few places in which whites and African Americans freely associated.

Despite the Savoy’s impactful start, it eventually waned in popularity and finally closed its doors for good in 1956. However, the impact of the Savoy on the Boston jazz scene cannot be overstated.. It not only hosted many of the era's more famous acts but launched the careers of Boston's biggest jazz stars. Thus, it is no wonder why Savoy is considered the venue where Boston jazz originated.

Citations

1. Nat Hentoff, "The Shape of Jazz That Was," Boston Magazine, last modified May 15, 2006.

2. George Frazier, "Someday Nick's Might Be 'Hallowed' Home of Jazz, Says Frazier," Down Beat Magazine, November 15, 1941, 6.

3. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles (Troy, NY: Troy Street Publishing, 2012)

4. Emily Sweeney, "77 years later, the mystery of the Cocoanut Grove fire remains unsolved," The Boston Globe, last modified November 27, 2019

5. GBH Archives, “Say Brother; Vaudeville; Remembering the Savoy Cafe,” March 21, 1976.

6. Nat Hentoff, "The Shape of Jazz That Was.”10. Ibid., 224, 225; Richard Vacca, “John Neves: ‘His Time Was Impeccable,’” Richard Vacca (blog), July 17, 2019.

10 Hi-Hat Club

572 Columbus Ave

1937 - 1955 (1948 - 1955, Integrated)

Historical Marker by Cassie Tanks, Ph.D. Student, World History

History

Here stood the Hi-Hat, a barbecue and nightclub that helped the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Columbus Avenue earn the name “The Jazz Corner.” Opened in 1937 by Julian Rhodes, the Hi-Hat became one of three clubs in the South End to be segregated. It catered to "white music" and white patrons only, despite being in a historically African American neighborhood. It claimed the title of "America's smartest barbecue" because the Hi-Hat prided itself on serving savory barbecue chicken in a classy setting. Top hats and canes were seen not only on the logo, but on the doormen and staff as well.

When Wally's opened down the block in 1947 and gained success, the Hi-Hat integrated and began to showcase Black musicians. This is regarded as the Hi-Hat's "Golden Era." Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, and Charlie Parker graced the Hi-Hat stage and dazzled audiences. Local legends, such as Dean Earl, drew big crowds and helped put Boston jazz on the map. Symphony Sid Torin, a renowned radio personality, broadcast from a special booth in the Hi-Hat and highlighted the artistry of Hi-Hat musicians.

In 1955, a fire shuddered the Hi-Hat and closed down the beloved club. But, its mark was not forgotten. When the Harriet Tubman House took over the location in 1975 it held "Hi-Hat Nite" fundraisers to support its community work. Many Hi-Hat artists performed at these fundraisers, including Sabby Lewis. In 2020 a development company bought the property and demolished the Harriet Tubman House1 to develop luxury condos.2

Citations

1. Arielle Gray, “‘Frustration, Disappointment and Hopelessness’: Boston Residents React to Demolition of Harriet Tubman House,” WBUR, December 11, 2020. https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/12/11/frustration-disappointment-and-hopelessness-boston-residents-react-to-demolition-of-harriet-tubman-house.

2. For a more detailed discussion of the Hi-Hat and Boston’s Jazz History more generally, see Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlight 1937-1962, (Belmont, Massachusetts: Troy Street Publishing LLC, 2012).

To read more history that informed this marker, see Jim Botticelli, Dirty Old Boston: Four Decades of a City in Transition, (Union Park Press, 2014); Nat Hentoff, “The Shape of Jazz That Was.” Boston Magazine, May 15, 2006. https://www.bostonmagazine.com/2006/05/15/the-shape-of-jazz-that-was/; and Drake Lucas, “South End Jazz: An Invisible Tradition.” Boston: City in Transition, 2004. https://journalism.emerson.edu/changingboston/south_end/index.htm.

11 Wally's Cafe Jazz Club

428 Massachusetts Ave (1947 - 1979)

427 Massachusetts Ave (1979 - PRESENT)

1947 - PRESENT

Historical Marker by Andres Garcia, Northeastern University

History

Wally's Cafe is one of Boston's most revered jazz clubs, perhaps the oldest club still standing today. Located at Jazz Square, the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Columbus Avenue, this historic venue has been a cornerstone of Boston's jazz scene since its inception. Established in 1947 by Joseph L. Walcott, an immigrant from Barbados, Wally's was the first black-owned jazz club in Boston and Walcott the first African American to hold a liquor license in the city. Despite having strong competition from clubs such as the Hi-Hat and Savoy, the club stood out as one of the few integrated jazz clubs in Boston, a club where black and white, where all audiences could mingle. Initially located at 428 Massachusetts Avenue, the club moved across the street to its current location, 427 Massachusetts Avenue, in 1979 as the Orange Line was built.

The Walcott-Pointsdexter family, Elynor Walcott, Frank, Lloyd and Paul Pointdexter, still own and run the club to this day. They have ensured that throughout jazz history, from the Bebop era until today, Wally's has stood as a strong pillar of the community. The club has hosted many different artists, big names such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillepsie or Billie Holiday, or local artists such as Mae Arnette, Fat Man Robinson, or Sabby Lewis. The club has allowed young musicians who are studying to thrive as they opened cheap housing for them above the cafe and continue to provide a space where young musicians can jam and hone their craft. Wally's is one major reason that the City of Boston designated the corner of Columbus and Massachusetts Avenues as Jazz Square. Wally's stands as a center for people who are jazz enthusiasts and for newcomers, allowing broad audiences to enjoy the art of jazz.

Citations

1. History – Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club, wallyscafe.com/history/; Camille Dodero, “We’re So Grateful Wally’s Café Jazz Club Still Exists,” Boston Magazine June 2024, https://www.bostonmagazine.com/arts-entertainment/2024/06/25/wallys-cafe-jazz-club-is-the-best/.

2. Home,” Black Artists of Boston, blackartistsofboston.org/artists/elynor-walcott/; https://blackartistsofboston.org/artists/frank-poindexter/; https://blackartistsofboston.org/artists/lloyd-poindexter/.

3. Dodero, “We’re So Grateful Wally’s Café Jazz Club Still Exists.”

4. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places and Nightlife, 1937- 1962 (Belmont: Troy Street Publishing, LLC, 2012), 149-155.

12 Eddie's Cafe

425 Massachusetts Ave

1947 - 1958

Historical Marker by Istiakh Ahmed, Ph.D. Student, Public Policy

History

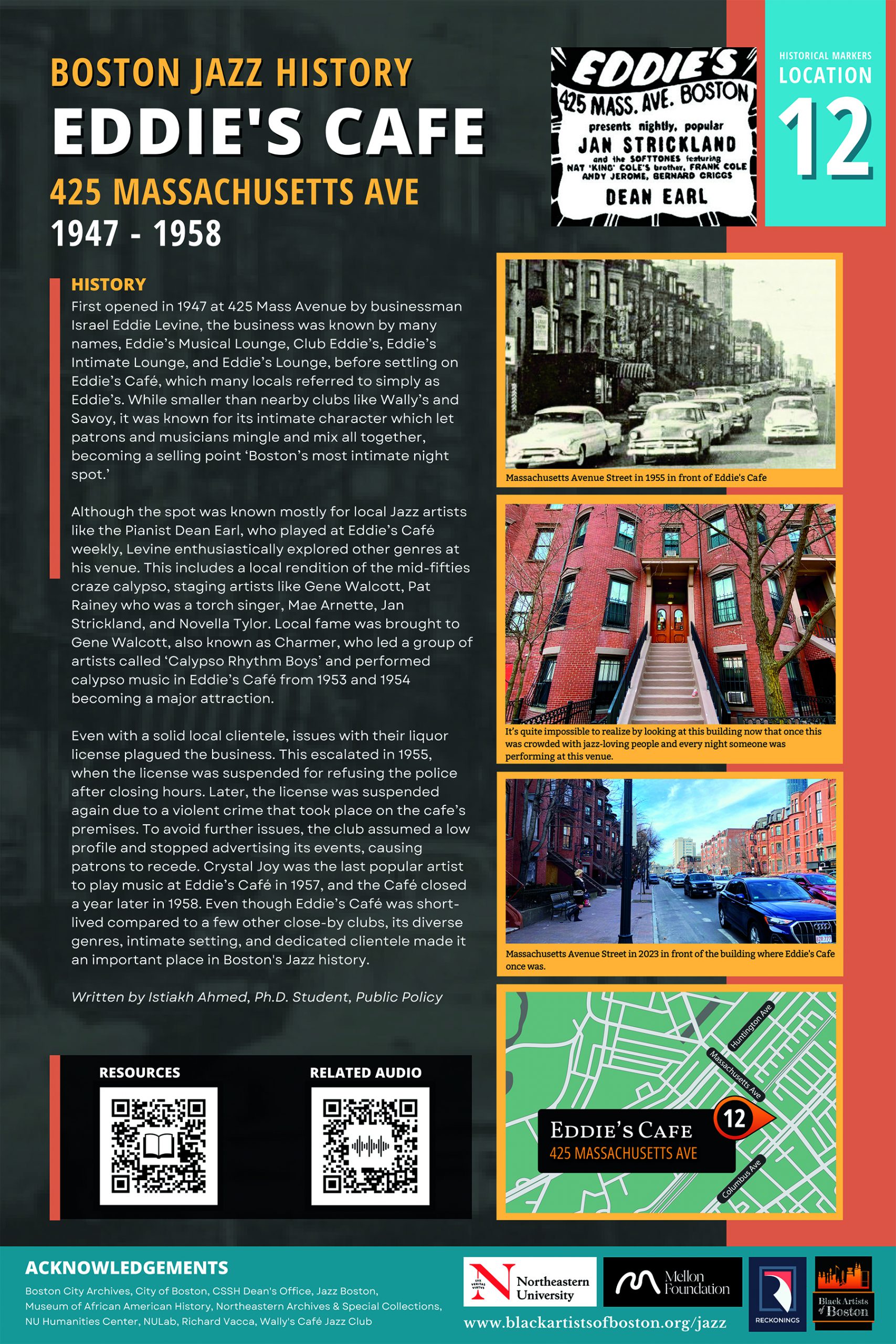

First opened in 1947 at 425 Mass Avenue by businessman Israel Eddie Levine,1 2 the business was known by many names, Eddie’s Musical Lounge, Club Eddie’s, Eddie’s Intimate Lounge, and Eddie’s Lounge, before settling on Eddie’s Café, which many locals referred to simply as Eddie’s. While smaller than nearby clubs like Wally’s and Savoy, it was known for its intimate character which let patrons and musicians mingle and mix all together, becoming a selling point ‘Boston’s most intimate night spot.’3

Although the spot was known mostly for local Jazz artists like the Pianist Dean Earl, who played at Eddie’s Café weekly,4 5 6 7 Levine enthusiastically explored other genres at his venue. This includes a local rendition of the mid-fifties craze calypso, staging artists like Gene Walcott, Pat Rainey who was a torch singer,8 Mae Arnette, Jan Strickland, and Novella Tylor.9 Local fame was brought to Gene Walcott, also known as Charmer, who led a group of artists called ‘Calypso Rhythm Boys’ and performed calypso music in Eddie’s Café from 1953 and 1954, becoming a major attraction.10 11

Even with a solid local clientele, issues with their liquor license plagued the business. This escalated in 1955, when the license was suspended for refusing the police after closing hours.12 Later, the license was suspended again due to a violent crime that took place on the cafe’s premises. To avoid further issues, the club assumed a low profile and stopped advertising its events, causing patrons to recede. Crystal Joy was the last popular artist to play music at Eddie’s Café in 1957, and the Café closed a year later in 1958.13 Even though Eddie’s Café was short-lived compared to a few other close-by clubs, its diverse genres, intimate setting, and dedicated clientele made it an important place in Boston's Jazz history.14

Citations

1. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Belmont: Troy Street Publishing, LLC, 2012), 137

2. Live Jazz? It’s dying here, man! Jazz in the South End, by Hope Shannon, Patch

3. Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles, 137

4. Ibid

5. Dean Earl Back at Eddie Levine’s, Boston nightclubs, Jazz History, by Richard Vacca, March 31, 1954

6. Dean Earl: “The Original Dean”. Boston Musician, Jazz History. By Richard Vacca

7. Dean Earl Back at Eddie Levine’s, Boston nightclubs, Jazz History, by Richard Vacca, March 31, 1954

8. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles, 138

9. Ibid

10. Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles, 139

11. The Charmer’s last gig. Jazz History. By Richard Vacca, August 29, 1955

12. Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles, 139

13. Ibid

14. Ibid, 138

13 Sandy's Jazz Revival

54 Cabot St, Beverly, MA

1931 - 1985

Laurel Schlegel, M.A. Student, Public History

History

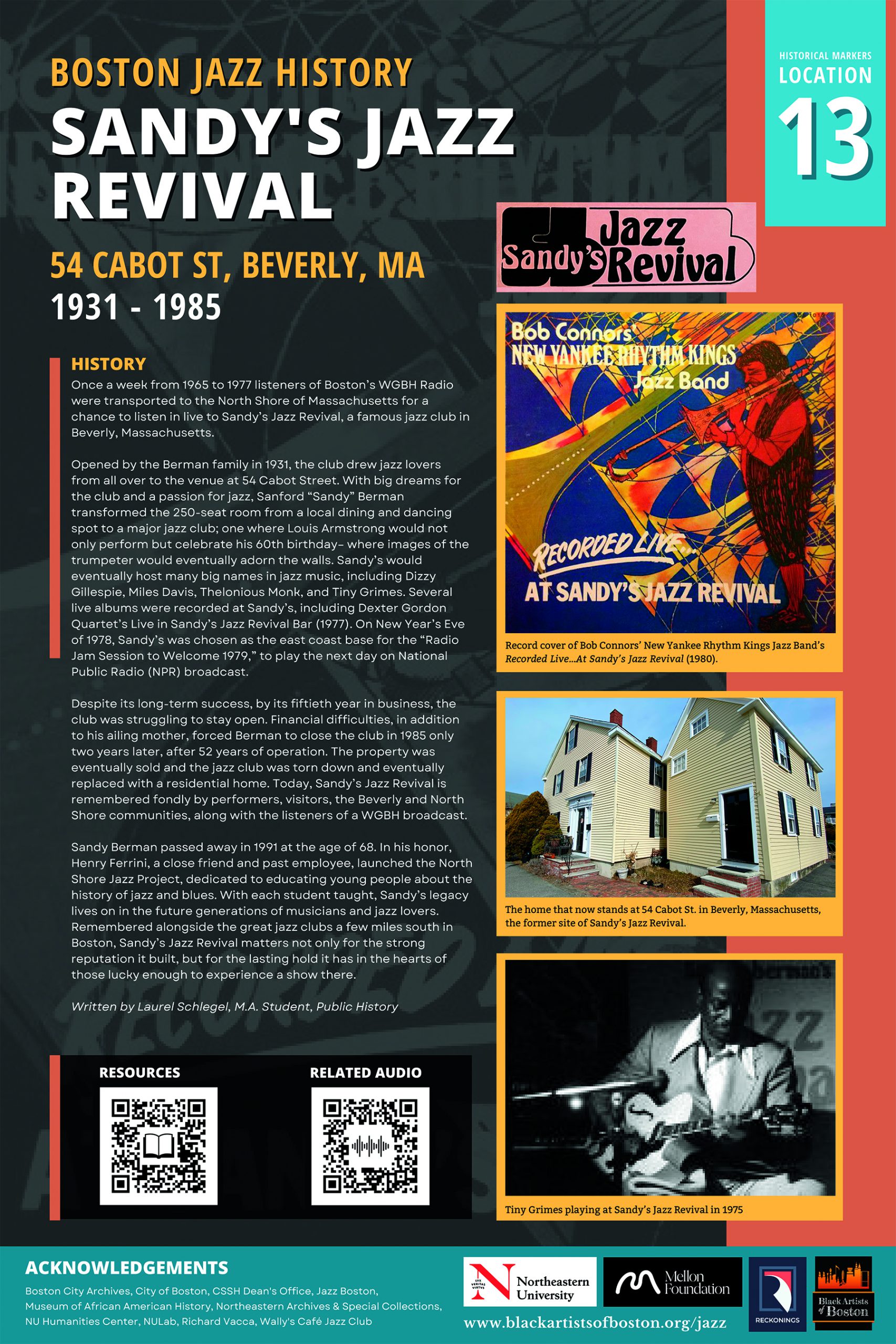

Once a week from 1965 to 1977 listeners of Boston’s WGBH Radio were transported to the North Shore of Massachusetts for a chance to listen in live to Sandy’s Jazz Revival, a famous jazz club in Beverly, Massachusetts.1

Opened by the Berman family in 1931, the club drew jazz lovers from all over to the venue at 54 Cabot Street. With big dreams for the club and a passion for jazz, Sanford “Sandy” Berman transformed the 250-seat room from a local dining and dancing spot to a major jazz club; one where Louis Armstrong would not only perform but celebrate his 60th birthday. Sandy’s would eventually host many big names in jazz music, including Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Tiny Grimes. Several live albums were recorded at Sandy’s, including Dexter Gordon Quartet’s Live in Sandy’s Jazz Revival Bar (1977).2 On New Year’s Eve of 1978, Sandy’s was chosen as the east coast base for the “Radio Jam Session to Welcome 1979,” to play live on National Public Radio (NPR) broadcast.3

Despite its long-term success, by its fiftieth year in business, the club was struggling to stay open. Financial difficulties, in addition to his ailing mother, forced Berman to close the club in 1985 only two years later, after 52 years of operation.4 The property was eventually sold and the jazz club was torn down and replaced with a residential home. Today, Sandy’s Jazz Revival is remembered fondly by performers, visitors, the Beverly and North Shore communities, along with the listeners of a WGBH broadcast.5

Sandy Berman passed away in 1991 at the age of 68. In his honor, Henry Ferrini, a close friend and past employee, launched the North Shore Jazz Project, dedicated to educating young people about the history of jazz and blues.6 With each student taught, Sandy’s legacy lives on in the future generations of musicians and jazz lovers. Remembered alongside the great jazz clubs a few miles south in Boston, Sandy’s Jazz Revival matters not only for the strong reputation it built, but for the lasting hold it has in the hearts of those lucky enough to experience a show there.

Citations

1. “Sandy’s Jazz Revival; Joe Williams,” 4/19/1977, GBH Archives.

2. D.S. Monahan, “Sandy’s Jazz Revival,” last modified December 1, 2022, Music Museum of New England.

3. “Radio Jam Session to Welcome 1979,” December 28, 1978, New York Times.

4. Monahan, “Sandy’s Jazz Revival.”

5. Charles Giuliano, “Hipster Filmmaker Henry Ferrini: From Jazz to Gloucester Writers’ Center,” February 1, 2017, Berkshire Fine Arts.

6. Larry Clafin Jr., “Sandy’s Legacy: North Shore Jazz Project aims to continue vision of Beverly Jazz Icon,” November 13, 2009, The Salem News.