INTRODUCTION

by Avery Ferro, M.A. Candidate, Public History, Northeastern University

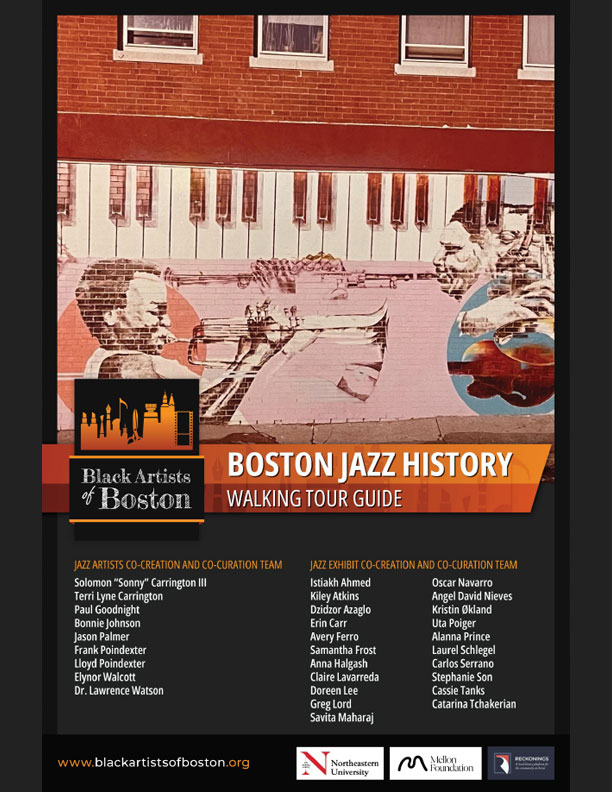

In 1982, Paul Goodnight painted his mural celebrating jazz music, “The Birth of Black Classical Music” on the wall of Walter Jo’s, a local club on Tremont Street. The mural featured jazz greats such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Sarah Vaughan. The piece was not only a tribute to the depicted jazz musicians but to the community itself, as Goodnight made a point to involve the local residents in its creation, even allowing children to participate. The mural was a beloved staple of the community. It was a shock then, when a short four years later the mural was whitewashed, seemingly out of nowhere and with no warning, by the property manager. Outrage rang out in the community – a testament to how much the mural meant to them. In fact, it wasn’t until community members urged him that Goodnight took action, suing at their behest the real estate firm who owned the property. As a result of this case, State Senator Edward Kennedy proposed the Visual Rights Art Amendment that would protect artists’ right to preserve their work in the United States, a piece of legislation that passed in 1990. Though this amendment was certainly a triumph, “The Birth of Black Classical Music” was already lost without having been properly preserved. The story of Paul Goodnight’s mural is a quintessential example of the importance of place and the preservation of community history. The mural was seen as a neighborhood landmark, and yet it was removed overnight – a piece of Boston history, and perhaps more importantly, the community’s history, gone, without notification or the chance to preserve it. However, it wasn’t just art that was lost when this mural was removed, it was yet another piece of jazz history wiped clean from Boston’s South End neighborhood. Goodnight saw the piece as encompassing “the kind of music, the kind of uplifting place this [Tremont street and the surrounding area] was.”

There was a time when the South End of Boston was home to a vibrant jazz scene with a variety of jazz clubs lining its streets. These clubs fostered community, welcomed some of America’s jazz greats, and nurtured prominent Boston jazz musicians. Yet, there is almost no trace of these spots today and little knowledge of this significant part of the city’s history. Only Wally’s remains standing, a lone testament to the lively jazz scene that once was. Since jazz is mostly intangible and community-driven, one of the most important parts of its history is place. When important jazz landmarks beloved by the community disappear, without consistent efforts to preserve their memory, we are in danger of erasing important legacies. This is why collective memory and the archiving and documenting of the people, places, and things that make up this memory, are so important and why Northeastern University’s course, Documenting Fieldwork Narratives, was created.

The class began when Professor Lee and Professor Nieves were tasked with creating a new course that would marry oral history and ethnography to help Northeastern graduate students develop ethnographic skills while also training them to integrate community members and values into their work. Partnering with local performance artist Dzidzor Azaglo and a group of community elders, the professors and students work to center the contributions of Boston’s black artists and build a repository of the artists and their work, but more importantly to listen to the stories of their lives and their significant contributions to Boston’s history. The Black Artists of Boston project reckons with the exclusion of marginalized communities in history, addressing the silences and gaps in the archiving, preservation, and general documentation of their lived experiences and histories. This portion of the project deals specifically with the impact and memory of place.

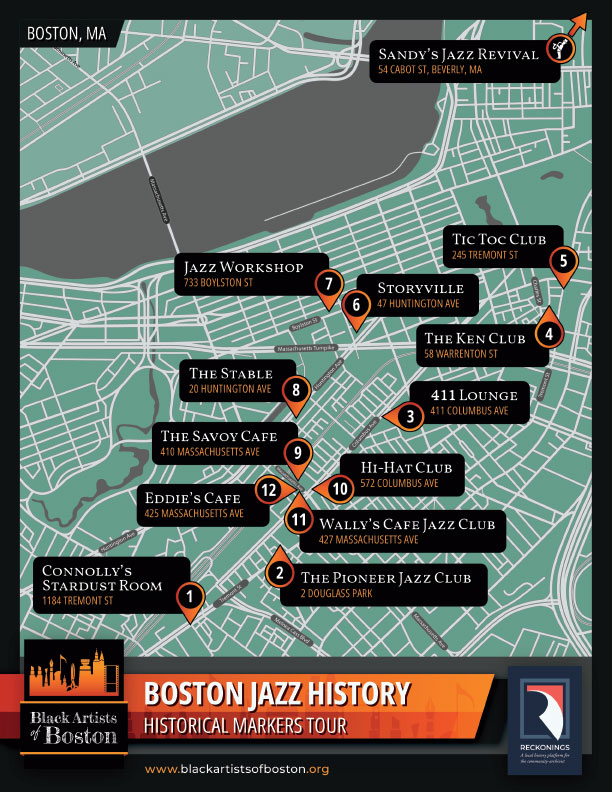

Here, then, is a guidebook that is the culmination of research conducted by the students in the class over the course of a semester on twelve prominent jazz clubs that are no longer in existence but which contributed to Boston’s rich, but little remembered, jazz history. In addition to this guidebook, twelve temporary historic markers have been placed at each site in the absence of the club itself. Let these markers be a reminder that the absence of these places is just as much part of the history of this community as the places themselves were when they were standing.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Alderman, Derek H. “‘History by the Spoonful’ in North Carolina: The Textual Politics of State Highway Historical Markers.” Southeastern Geographer 52, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 355-73.

Burnett, John, and Marisa Penaloza. “The National Park Service expands its African-American history sites.” NPR. Last modified June 26, 2022.

Leggs, Brent. “Growth of Historic Sites: Teaching Public Historians to Advance Preservation Practice.” The Public Historian 40, no. 3 (August 2018): 90-106.

Robbins, Christine Reiser, and Mark W. Robbins. “Engaging the Contested Memory of the Public Square: Community Collaboration, Archaeology, and Oral History at Corpus Christi’s Artesian Park.” The Public Historian 36, no. 2 (May 2014): 26-50

Teal, Kimberly Hannon. Jazz Places: How Performance Spaces Shape Jazz History (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021).