So, being an artist, I never looked at it for the fame of it, so to speak. I just knew it was a purpose. For me to do it, to be. And then I'm like "but… I need money. I want to be famous!" But now I see what the purpose is, because you develop this energy, this force, that exudes this creativity with individualism, that's different. And it took me a long time to accept that. [...] Because we all come in on this planet to be expressive of our purpose, and to be individual. We all have our own journeys. And I think that's very hard for a lot of people to accept.

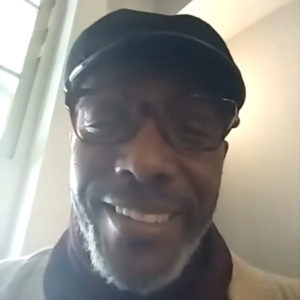

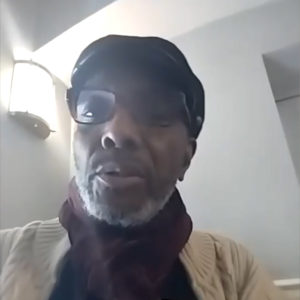

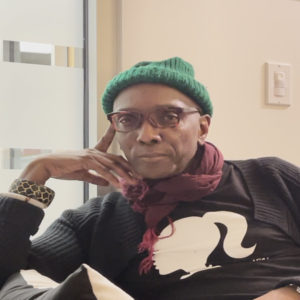

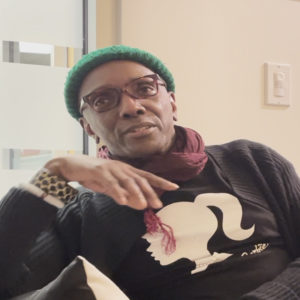

”About Dale Patterson

Boston community creative Dale Patterson was interviewed late in the winter of 2022 in Dr. Angel David Nieves’s office at Northeastern University in Boston. Patterson represents himself as an artist: folk artist, Renaissance man, futurist, Black artist, appreciator, historian, and activist. He describes how he collects: objects speak to him, in matters of color, stripe, shape, and lately he has been focusing on drag queen imagery. Understood in the arts community and marketplace as a crafter and dollmaker, he shared the following:

Patterson is New York State born and raised, growing up in Ossining, NY on the Hudson River. His mother was a creative herself: she had gone to Juilliard, and picked up on his affinity/interest in art. Sensing that he was a creative, perhaps a dancer, she started permitting him overnights in NYC at about age 18: Patterson stayed with an uncle who lived on 47th Street in Manhattan, visited Harlem, but the Village was his favorite neighborhood and hangout.

While Patterson’s reputation has been that of crafter, he has also worked in performance: studying and participating locally in Afro-Cuban dance, and ballet, and acting in African-American repertory theater. Recalling his days of theater and performativity, Dale alluded to larger-than-life performers, and local LBGTQ theater. Of his journey finding himself between African American and queer theater, he described putting on his “black hat” in African American theater, and his “queer hat” when he is acting and participating in queer theater, easily distilling the compartmentalization of human experience he has known.

He describes suffering from self-hate as he grew up queer and draws distinctions from his queer experience and from others’ gay experiences. However, his mother on her deathbed affirmed her acceptance of him and reaffirmed her love for him, and during the interview Patterson shared that “if Mom could get over it [then] fuck the world and I’s free.” His motto is: “I’m here and I’m queer and queers are everywhere” and of his sexuality he shared that back in the day – he is 65 years old now – lesbians were his people. Although he was not admitted to all women’s clubs, he feels his Blackness helped him maneuver lesbian spaces.

Patterson left NYC during the AIDS epidemic, describing a generation there that was almost wiped out. When asked how he has described/depicted Boston he acknowledges that historically communities here are separate: Black, white, always separate. However, there is creativity in Boston and Dale admits that “this [Boston] is home.” He has had a chance to spread his wings during his time here: he’s traveled to France, Italy, and the Caribbean and still manages to return and walk the streets of NYC to refuel. He describes an arts scene every summer in Provincetown with an abundance of energy flowing there. In particular, of the arts scene back in Boston at his former home at the Piano Factory Building on Tremont Street, he says of the place that it was a hub: both housing and art gallery and describes it as having a “nice mix of folk” from 1980’s forward to 2010s. Recalling gentrification as a sore spot, after the Piano Factory no longer received government aid and the place went market rent, he witnessed a long march of people leaving the building, ultimately including himself. Management at the Piano Factory would protect established artists, but Patterson described a man’s world, a men’s club and mostly straight, and if not straight, not out. Patterson has since suffered the trauma of re-location and now lives in a space the tenth of the size of his old studio. Moving from the Piano Factory, he put his collections and what he could into storage and, subsequently, he lost the storage. All in all, he recalls the experience as having “destroyed my whole life.”

While Patterson has been no stranger to trauma – he has previously worked in infectious disease at the Centers for Disease Control, a portfolio that includes HIV and especially men who had sex with men – he has become more reclusive during the pandemic and post-move from the Piano Factory. Patterson describes himself as emerging from trauma (he says he’s now on the far side of it), and is now imagining how he will more actively return to his art. With struggle behind him (he’s effectively renounced it), and understanding that Boston remains segregated, with no particular creative platform, Patterson envisions digitally marketing a small digital gallery of his work. Remembering how Paul Goodnight, taught him an appreciation of Black art, Patterson is now imagining how he will leave his own legacy.